The Interloper

We've had tons of rain, finally got a clear night to photograph the comet

Astronomical imaging in the Pacific Northwest is tough. Rain, then rain, then more rain, then clouds, then more rain—that’s the pattern from September to June. Clear nights are rare, and even then there may be so much moisture in the air that you still don’t get the greatest images.

So last night was a rare treat: cloud free, not horrid humidity, and all I had to contend with was the light pollution to the west. Which is not minor; the largest concentration of shopping malls and excessive lighting is directly to my west, and it never gets very dark.

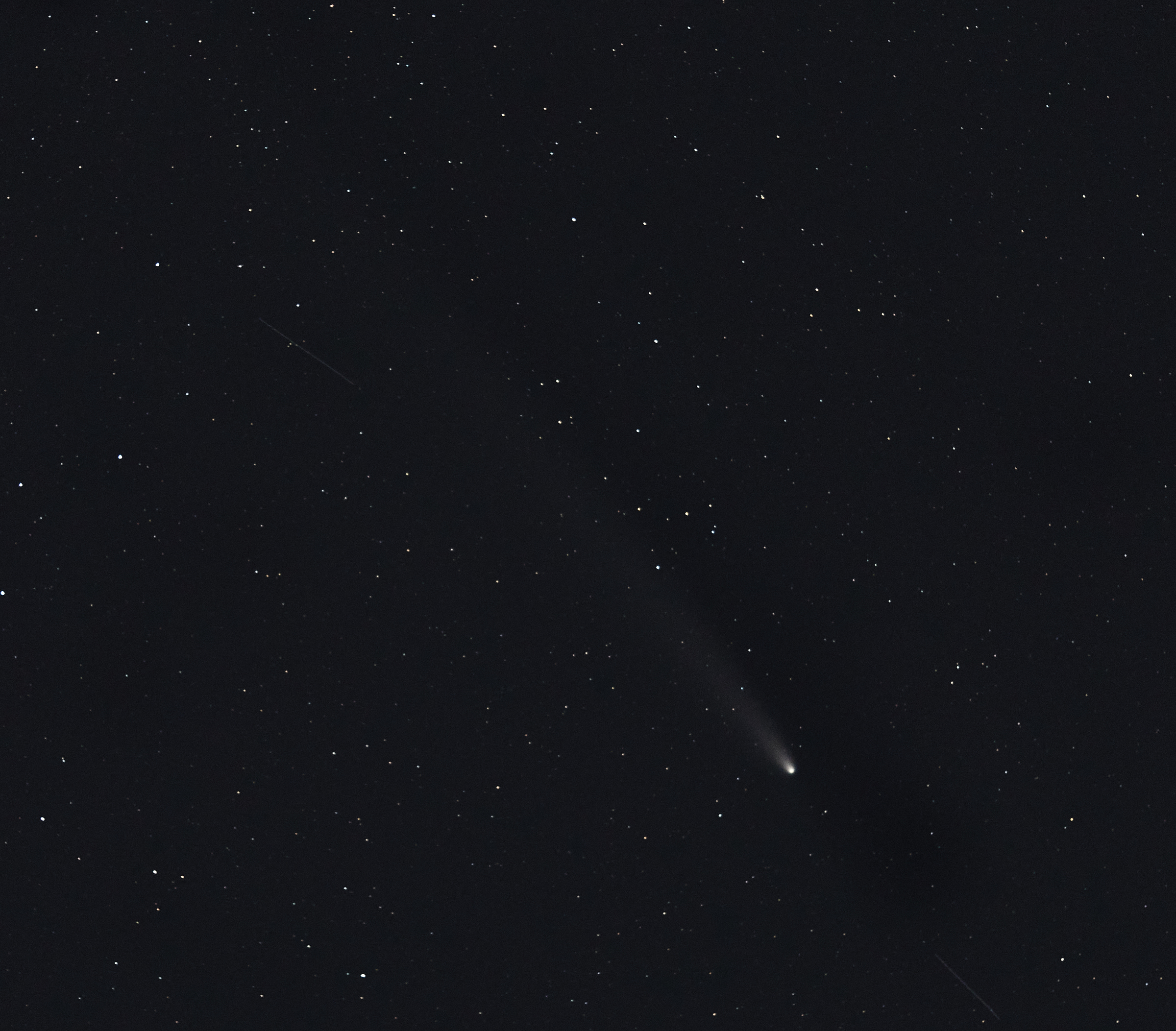

Still, as you can see above, I got a photo of Comet C/2023 A3 Tsuchinshan-ATLAS. It was tiny (it is now further from the sun, so dimmer). It was dim compared to the commercial lights—it was not visible to the naked eye, so magnitude was presumably no more that 4 or 5, perhaps even dimmer. But it did show up photographically.

The shot above was made with my Sony A9III camera and a Canon EF 200mm f/2 lens. I did not set up for tracking (I have only a very clumsy Benro tracker which I seldom have the patience to use), so short exposures fortunately worked OK. The shot above was at ISO 1000 and for two seconds. (Any longer, and the stars and comet would be elongated from their motion relative to the spinning earth.)

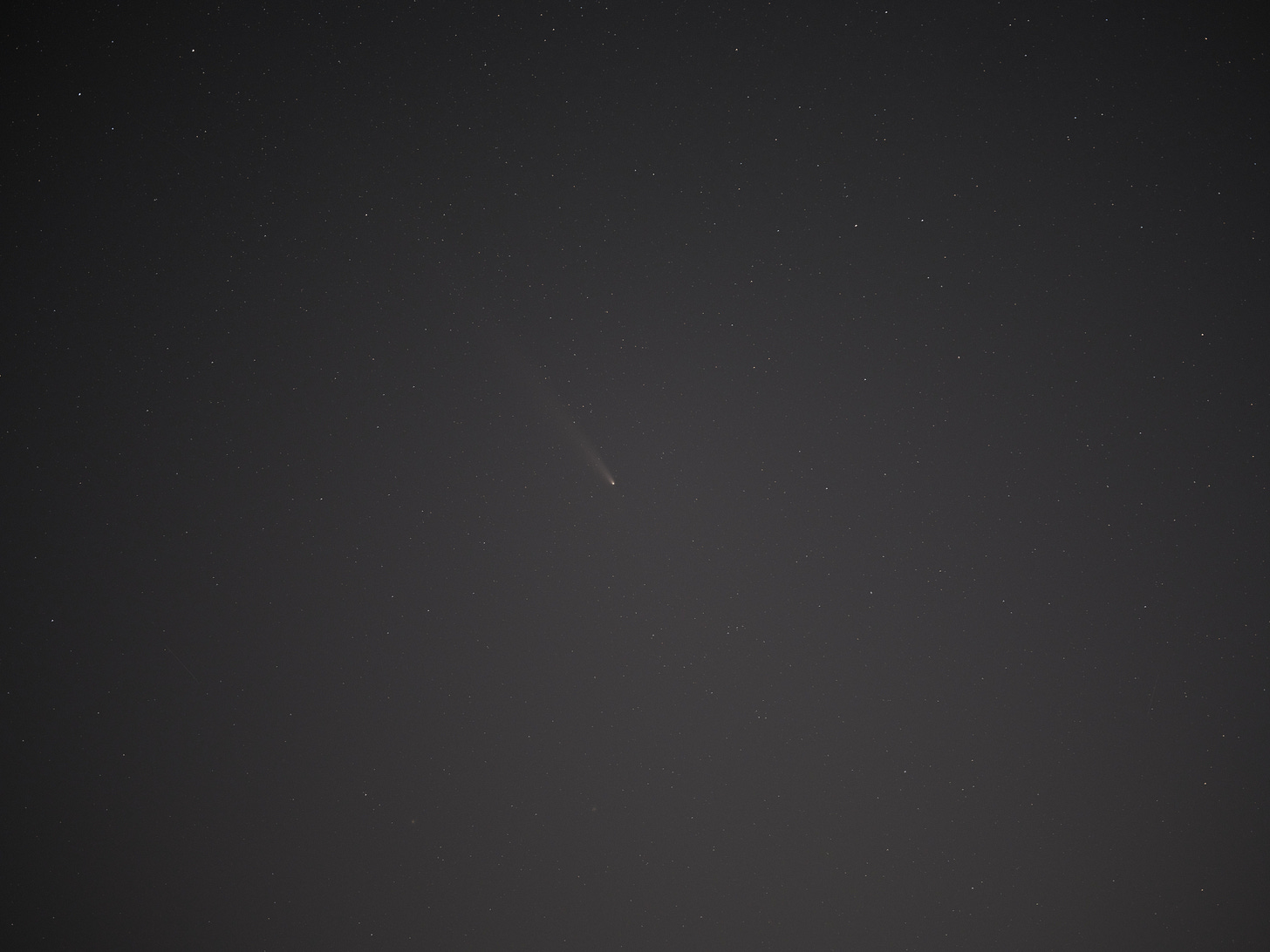

How dim and small was the comet, really? The wide-angle shot above, made with the Fuji camera and a zoom lens at 21.5mm focal length, shows just how tiny it was on the sky. This was shot at f/4, 8 seconds, and at ISO 3200. So that’s a really long exposure compared to the Sony shot at the top. I did quite a bit of image processing cleanup to get a reasonable image out of the data. The comet, if you are having trouble spotting it, its a little below center.

If you have a good eye, you can just make out the brightest portions of the Milky Way above the comet. They are most noticeable toward the left edge, but extremely faint. We can seldom see the Milky Way from our house, even to the east; there’s just too much light pollution. I would have to drive about a hundred miles east to see a significant improvement on the other side of the Cascade Mountains.

I also took a photo of the comet with a 110mm f/2 lens on the Fuji camera (a GFX 100S II). The result is similar to the Sony with 200mm, though not as detailed due to the shorter focal length.

That’s an unedited image. It shows the light pollution in two ways: as a circular gradient due to vignetting in the lens, and a vertical linear gradient inherent in the light pollution (it was brighter closer to the horizon).